LAHORE: When multinational consumer goods company Procter & Gamble (P&G) announced earlier this month that it would discontinue its manufacturing and commercial operations in Pakistan, the reaction was loud and familiar. Headlines spoke of a “corporate retreat,” analysts warned of an “investor exodus,” and the narrative quickly hardened into one of crisis.

It was not the first announcement of its kind. In recent years, several major companies, including Shell, TotalEnergies, Uber, Careem, Pfizer, Sanofi, Microsoft, Bayer, Eli Lilly, and Viatris, have all scaled down or shut their operations. A picture emerged — or at least was painted — of foreign companies fleeing an increasingly hostile business climate.

But beneath the noise lies a more complicated story. Yes, some of the reasons are distinctly Pakistani, but others are global. And while the language around Pakistan is often alarmist, similar corporate restructuring in India or the United Kingdom is framed in much softer tones.

Real problems, misleading narratives

P&G’s decision is emblematic of the current moment. While the company is shutting down its on-ground operations, it is not disappearing. Its products will remain on shelves through a leaner distributor model — a move designed to cut costs without abandoning the market altogether.

Shell’s withdrawal from the retail fuel segment tells a similar story. The decision, often framed as a verdict on Pakistan’s investment climate, is in fact part of a global strategic shift as the company pivots toward LNG and other energy priorities. TotalEnergies has made similar moves elsewhere.

Other sectors, particularly pharmaceuticals and fast-moving consumer goods, face sector-specific pressures. Delays in price controls, weak enforcement of intellectual property rights, and aggressive undercutting from local competitors have made it difficult for foreign brands to compete. Currency depreciation and an unpredictable tax regime have eaten into margins, and profit repatriation has become more cumbersome in recent years, further reducing corporate appetite.

These are real challenges. Pakistan’s policy environment remains volatile, the rupee unstable, and the tax burden heavy. Regulatory predictability— essential for long-term foreign investment — is still lacking. As a result, many companies are opting for smaller operational footprints or adopting distributor-led or franchise models instead of maintaining extensive on-ground presences.

It’s not just Pakistan

What’s missing from much of the public debate is the global context. Corporate restructuring is happening everywhere. The same companies reducing their footprint in Pakistan are making similar moves in other markets.

Shell has exited retail operations not just here but also in Mexico and Indonesia. Pfizer and Eli Lilly have scaled back globally as the pharmaceutical industry undergoes consolidation. Uber has pulled out of or reduced operations in several non-core regions. Microsoft’s decision to wind down its local entity mirrors similar retrenchments in smaller markets worldwide.

What’s unique is not the corporate strategy — it’s the way the story is told.

India: Outflows without panic

This year alone, the Financial Times reported that foreign investors have pulled $17 billion from Indian equities, the largest outflow in the country’s history. The rupee has fallen 3.6% against the dollar. India is facing weak earnings, global tariffs, and stretched valuations.

Yet the tone of coverage is measured. It’s called a “market correction,” a “cycle,” an “adjustment.” Analysts speak of short-term pain, not systemic collapse.

Corporate restructuring in India is cushioned by market depth, government response, and, crucially, media framing. Even when large players pull back, the story is told in the language of strategy, not catastrophe.

UK: Same moves, softer words

Across the world, the London Stock Exchange has lost 213 listed companies since 2016, amounting to more than £300 billion in market capitalization. Companies are choosing to list elsewhere, private firms are buying out public ones, and investor flows are shifting.

But this too is described as a “turning point,” not an exodus. There’s talk of structural shifts, not market failure. A country with strong institutions and financial depth can absorb exits without triggering national panic.

Pakistan’s narrative

Three factors help explain the contrast.

First, perception is shaped by context. In India or the UK, exits happen against a backdrop of financial depth, strong institutions, and consistent inflows. In Pakistan, where foreign direct investment is low and growth fragile, each exit feels magnified.

Second, media framing matters. In countries with greater economic confidence, corporate departures are interpreted through the lens of strategy. In Pakistan, they are often read as symptoms of decline.

Third, capital scarcity amplifies impact. When inflows are limited, outflows carry outsized weight. One high-profile departure can dominate headlines for weeks, reinforcing the narrative of crisis.

None of this is to deny Pakistan’s investment challenges. They are real, structural, and urgent, but the narrative of “flight” also misses the other half of the story.

While some firms have exited or restructured, others are entering or expanding — Saudi Aramco, Wafi Energy, Shanghai Electric, Gunvor Group, Barrick Gold, BYD, Strategic Metals, Etisalat, and more. Their investments target energy, mining, technology, and telecommunications — strategic sectors with long-term potential.

This dual reality — exits and entries, retrenchment and investment — defines Pakistan’s position in global capital flows. It is neither uniquely doomed nor uniquely safe. It is simply one of many markets undergoing realignment in a volatile global economy.

When a multinational restructures in Pakistan, the story is often told as if it were a national referendum. But when similar moves happen in India or the UK, they are framed as strategy, not surrender. The exits are real. The problems are real. But so too are the opportunities — and the global forces driving change.

Latest News

Israel’s West Bank ‘mega land grab’ draws international outrage

25 MINUTES AGO

.jpg)

'Godfather' and 'Apocalypse Now' actor Robert Duvall dead at 95

2 HOURS AGO

.jpg)

Sri Lanka's Nissanka leaves Australia on brink of T20 World Cup exit

5 HOURS AGO

.jpg)

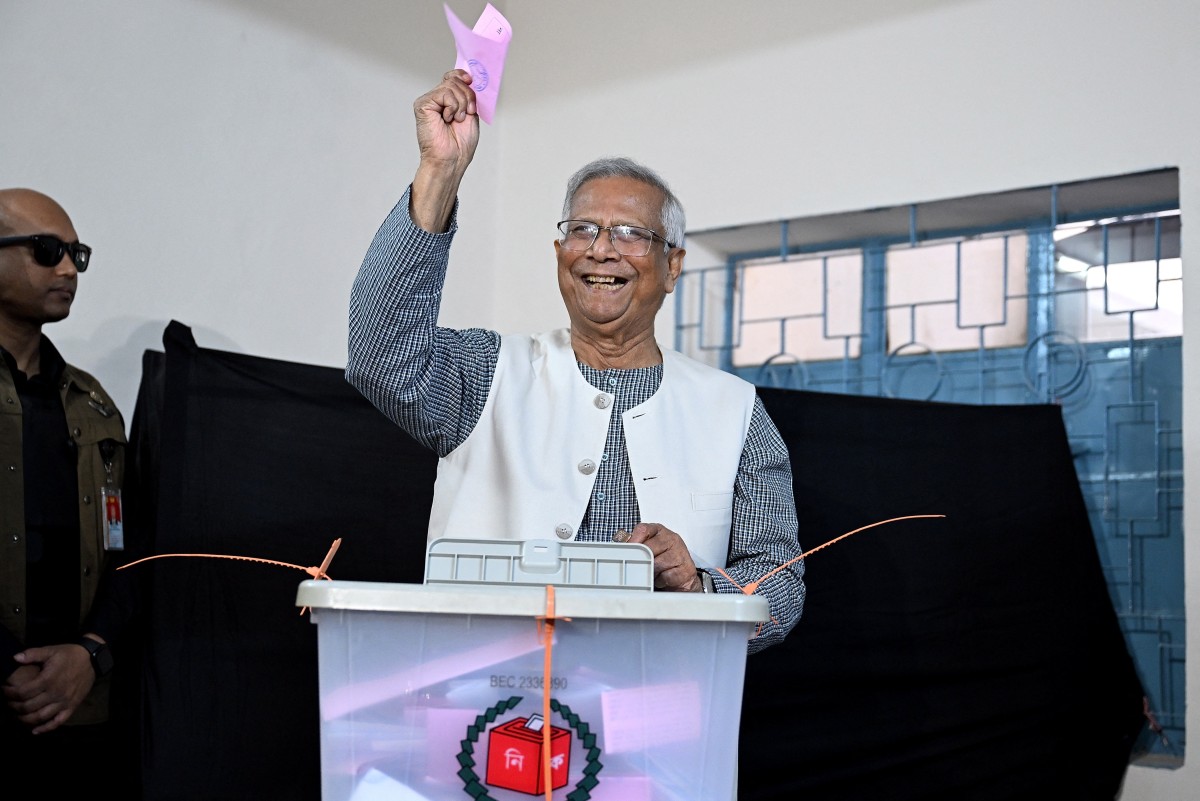

Bangladesh's Yunus announces resignation, end of interim govt

8 HOURS AGO

X hit by 'international outages': monitors

8 HOURS AGO

.jpg)